What is Peto's Paradox

Peto’s Paradox is named after epidemiologist Richard Peto, who noted the relationship between time and cancer when he was studying how tumors form in mice. Peto observed that the probability of cancer progression was related to the duration of exposure to the carcinogen benzpyrene [1]. He later added body mass to the equation, when he wondered why humans both contain 1000 times more cells and live 30 times longer than mice, yet the two species do not suffer incredibly different probabilities of developing cancer [2]. Further, cancer was not a major cause of mortality for large and long-lived wild animals, despite the increased theoretical risks. How can this be?

Why is it a paradox

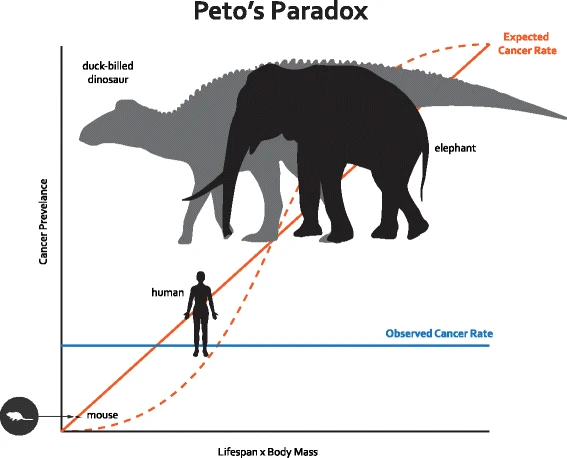

In a multicellular organism, cells must go through a cell cycle that includes growth and division. Every time a human cell divides, it must copy its six billion base pairs of DNA, and it inevitably makes some mistakes. These mistakes are called somatic mutations. Some somatic mutations may occur in genetic pathways that control cell proliferation, DNA repair, apoptosis, telomere erosion, and growth of new blood vessels, disrupting the normal checks on carcinogenesis [3]. If every cell division carries a certain chance that a cancer-causing somatic mutation could occur, then the risk of developing cancer should be a function of the number of cell divisions in an organism’s lifetime [4]. Therefore, large bodied and long-lived organisms should face a higher lifetime risk of cancer simply due to the fact that their bodies contain more cells and will undergo more cell divisions over the course of their lifespan (Fig. 1). However, a 2015 study that compared cancer incidence from zoo necropsy data for 36 mammals found that a higher risk of cancer does not correlate with increased body mass or lifespan [5]. In fact, the evidence suggested that larger long-lived mammals actually get less cancer. This has profound implications for our understanding of how nature has solved the cancer problem over the course of evolution.

How does one go about solving the paradox

From one perspective, the solution to Peto’s Paradox is quite simple: evolution [6]. When individuals in populations are exposed to the selective pressure of cancer risk, the population must evolve cancer suppression as an adaptation or else suffer fitness costs and possibly extinction. But that only tells us that evolution has found a solution to the paradox, not how those animals are suppressing cancer. Discovering the mechanisms underlying these solutions to Peto’s Paradox requires the tools of numerous subfields of biology including genomics, comparative methods, and experiments with cells. For instance, genomic analyses revealed that the African savannah elephant (Loxodonta africana) genome contains 20 copies, or 40 alleles, of the most famous tumor suppressor gene TP53 [5, 7]. The human genome contains only one TP53 copy, and two functional TP53 alleles are required for proper checks on cancer progression. When cells become stressed and incur DNA damage, they can either try to repair the DNA or they can undergo apopotosis, or self-destruction. The protein produced by the TP53 gene is necessary to turn on this apoptotic pathway. Humans with one defective TP53 allele have Li Fraumeni syndrome and a ~90% lifetime risk of many cancers, because they cannot properly shut down cells with DNA damage. Meanwhile, experiments revealed that elephant cells exposed to ionizing radiation behave in a manner consistent with what you would expect with all those TP53 copies—they are much more likely to switch on the apoptotic pathway and therefore destroy cells rather than accumulate carcinogenic mutations [5, 7].

How many different sollutions of the paradox are there

There are likely many solutions to Peto’s Paradox in nature, because large body size has evolved independently so many times across the history of life. We know that whales did not evolve the extra copies of TP53 like elephants [8, 9]. In fact, there is no evidence that whales evolved extra copies of any tumor suppressor gene—even the gigantic bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus), which has a lifespan of over 200 years [9]. In populations, large body size is often associated with higher fitness, conferring greater access to resources or mates and better predator avoidance. It is not surprising, therefore, that large body size has evolved again and again throughout evolutionary time—a trend first realized in the fossil record and known as Cope’s Rule [10]. Cope’s Rule applies widely across life from diverse marine taxa [11] to the extinct giant dinosaurs [12]. Large body size has evolved independently in 10 of the 11 placental mammalian orders [13]: think polar bears and hippopotami, walruses and giraffes, elephants and whales. Since many lineages faced the trade-off between large body size and cancer risk during their evolution, there have likely been many different pathways in which cancer suppression has evolved.